The Relevance & Power of the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize, arguably one of the most prestigious awards for humanity, is awarded to a person or organization who within in the past year, in the words of Alfred Nobel, “[has] done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

Peace work and its close relative, humanitarian work, is justifiably associated with humility. Peace work lends a connection to virtues that are giving, virtues kindred with the actions and intent leading to the betterment of humanity. It’s considered distasteful and directly oppositional to perform these acts for selfish reasons and/or ulterior motives. Giving a prize for these selfless acts, then, seem rather counterintuitive. What role does the prize have in promoting peace work? Does it have a role at all or is it an overrated political plaything for the international elite? Does the prize matter and has it inspired change?

An Overview

The Nobel Prizes were established more than 100 years ago by Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel through statements from his will. With no explanation as to why peace was made a category, the original intent behind the Nobel Peace Prize has remained unclear. What may shine a partial light on the intent is the mechanisms of the peace prize, as it was emphasized that the prize only recognize peace work from within the past year. An inventor, businessman, and philanthropist, among many other things, perhaps Alfred implemented this requirement as a commitment towards the importance of ongoing, rather than completed, work. Considering only work done within the last year reduces barriers keeping younger and/or newer peace workers in being recognized.

A Case Study: 2020 Nobel Peace Prize Recipient

Looking at the prize in the context of today, a case study demonstrates how the meaning and impact of the prize has aged. This year’s Nobel Peace Prize Recipient is the World Food Program (Programme if you’re British). As the food-assistance branch of the United Nations and the world’s largest humanitarian organization, the WFP has stated to receive the award “for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.”

As hunger and war are inextricably linked, the World Food Program does represent peace work in a very obvious way (for more on the relationship between hunger and war: “Hunger and War” from National Geographic). However, what does this prestigious and widely publicized prize do for the causes it celebrates? In this case, how would the awarding to the World Food Program contribute to the peace work considering food insecurity?

The Nobel Peace Prize does not solve food insecurity nor was it ever intended to. An inherently passive event, its only action is in announcing and giving an award. With its publicity and prestige, however, this action holds a lot of power in creating attention where it may have lacked before. In this regard, the greatest purpose in the Nobel Peace Prize seems to be in shining a light on individuals and organizations working towards peace and in the underlying messages that may be deduced from each particular recipient. During the announcement of the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize Recipient, the Nobel Committee Chairwoman, Berit Reiss-Andersen, stated that “with this year’s award, the Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to turn the eyes of the world towards the millions of people who suffer from or face the threat of hunger.”

With the World Food Program being a branch of the United Nations, it is inherently a cooperative and international program. With this in mind, the underlying message in the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize seems to be in support of internationalism and unification. Commenting on this year’s recipient, David Snyder from the Atlanta Peace Initiative (as well as a professor teaching a course on the Nobel Peace Prize) stated that “food is a symbol of larger concerns about internationalism. Nationalism in its various forms is the cause of war. Internationalism is the solution to war.” In the announcement speech of the 2020 recipient, Chairwoman Reiss-Andersen specifically endorsed international and multilateralism and condemned the divisive forces of nationalism and populism, stating “multilateral cooperation is absolutely necessary to combat global challenges, [it] seems to have a lack of respect these days and the Nobel Committee definitely wants to emphasize that.” In this regard, the Nobel Peace Prize intends to serve as a symbol towards unification and global cooperation.

Tangential towards global cooperation, the inoffensive nature of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize choice is also subject to criticism. The Nobel Peace Prize is no stranger to combative choices and its markedly uncontroversial recipient in a markedly controversial year seems very blatant. In this manner, it seems this year’s choice was more of a diplomatic one than a political one, as this past year has also seen pressing action concerning matters such as the refugee crisis and climate change. A consideration to take, however, is the interconnectivity between food and several global crises. The broad nature of this year’s recipient can either be taken as shying away from important conversation or as addressing all these crises on a base level. Within the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize Announcement, Chairwoman Reiss-Andersen stated that

“the link between hunger and armed conflict is a vicious cycle: war and conflict can cause food insecurity and hunger, just as hunger and food insecurity can cause latent conflicts to flare up and trigger the user of violence.”

Another, broader, criticism is in the scope of what counts as peace work. Peace work and humanitarian work are not synonymous and the Nobel Peace Prize tends to only recognize the latter. An argued negative effect of humanitarian is in its reactive, rather than proactive, nature: because humanitarian aid does not explicitly address the problem and only treats the symptoms, it makes conflict more bearable and therefore more likely. On the other hand, as stated above, hunger and war hold a cyclical relationship and addressing food insecurity could contribute to preventing conflict. This dilemma is not isolated solely to Nobel Peace Prize recipients and peace initiatives constantly need to find the balance between relief and its more proactive and sustainable partner: development.

Another underdeveloped aspect in peace and peace work is its relationship to human rights/justice. Julia Irwin from the Atlanta Peace Initiative states that “the line between humanitarian and human rights and peace and development are very blurry.” A question on the philosophical side: can there be true peace without justice? If the question is no, then it seems the implicit definition of peace needs to be expanded as well as the scope of peace work.

Note: The politics of the Nobel Peace Prize

As a geopolitically smaller state, the Nobel Peace Prize gives Norway a disproportionately large global voice. The Nobel Peace Prize is arguably one of the greatest global soft power assets due to its prestige and media attention. Because of its ties to a particular country (Norway), its no surprise the prize has been used to underhandedly criticise nations and make widespread commentary.

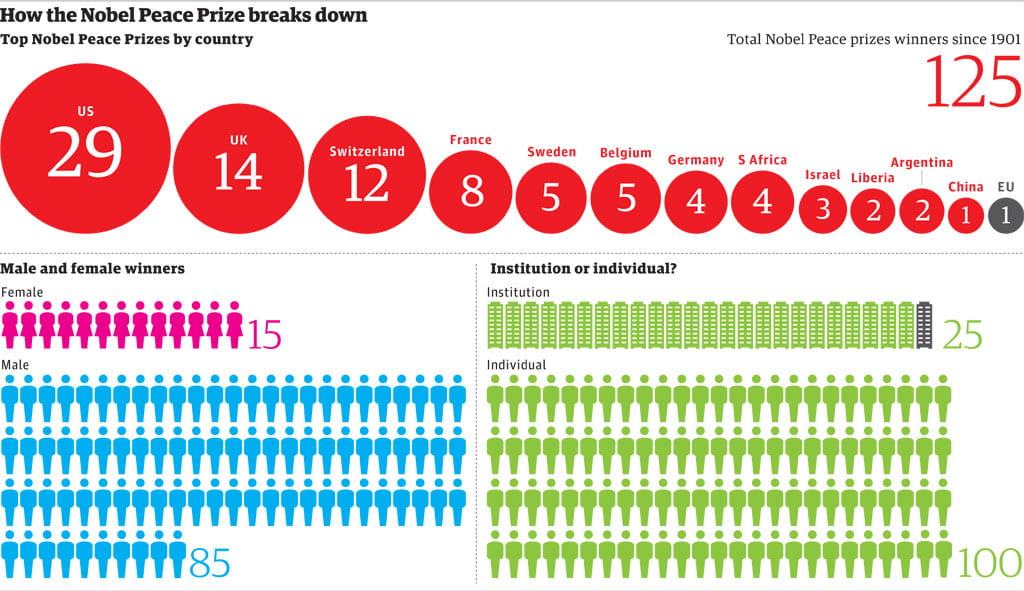

Notably, is the love-hate relationship the Nobel Peace Prize shares with America. No country has more Nobel Peace Prize recipients than America, however, no country has been criticised or “called out” more through Nobel Peace Prize choices than America.

Notable Controversies

1973: Le Duc Tho

Le Duc Tho was born in 1911 in Vietnam. He is a Vietnamese politician and an adviser to North Vietnam, who negotiated a cease-fire agreement with U.S. official Henry Kissinger during the Vietnam War. He was awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize at the age of 62, jointly with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. They were awarded the Prize for negotiating the Vietnam peace accord. Le Duc Tho refused accepting his award, claiming that the peace has not been established. He stated that:

“However, since the signing of the Paris agreement, the United States and the Saigon administration continue in grave violation of a number of key clauses of this agreement. The Saigon administration, aided and encouraged by the United States, continues its acts of war. Peace has not yet really been established in South Vietnam. In these circumstances it is impossible for me to accept the 1973 Nobel Prize for Peace which the committee has bestowed on me. Once the Paris accord on Vietnam is respected, the arms are silenced and a real peace is established in South Vietnam, I will be able to consider accepting this prize. With my thanks to the Nobel Prize Committee please accept, madame, my sincere respects.” (view source)

Thus, Le Duc Tho became the first person who had rejected the Nobel Peace Prize. The war in Vietnam continued despite Tho and Kissinger’s work, and it lasted more than a year. Many argued that Tho and Kissinger had not stopped the war.

“The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho is like granting Xaviera Hollander (the Happy Hooker) an award for extreme virtue.” – Stated by a TIME reader (view source)

1973: Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger is an American politician, diplomat, and he served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presidential administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. He was jointly awarded the prize in 1973 along with North Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho for brokering a cease-fire.

The award was highly criticized, not least because Kissinger had ordered a bombing raid of Hanoi while negotiating the cease-fire. Le Duc Tho declined his half of the award and two members of the committee, who had voted against Kissinger’s selection, resigned in protest.

1994: Yasser Arafat

Yasser was a Palestinian political leader. He was Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization from 1969 to 2004 and President of the Palestinian National Authority from 1994 to 2004. He and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres shared the 1994 award for their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.

The decision of awarding Arafat received criticism, not only because the awards are generally seen to have failed at ending the Israel-Palestine conflict, but also because of Arafat himself.

A member of the committee, Kare Kristiansen, resigned over Arafat’s nomination, and in an article for the Times of Israel in 2012, American columnist Jay Nordlinger called Arafat “the worst man ever to win the Nobel Peace Prize.”

2009: Barack Obama

Barack Obama is an American politician and attorney who served as the 44th president of the United States. He received the prize only 9 month after his first term.

The primary reason for giving the prize is that “the committee thought the prize would strengthen the president, but that it didn’t have this effect. ” stated by the former director of Nobel Institute, Geir Lundstad regrets his decision in 2015. And the award is also for his “”extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between people”.

Many people criticized his nomination for being premature and he had not been in power long enough to deserve the prize. Obama has only been in office less than a year, and has as yet no concrete achievements in peace making by the time he received his award.

“The Nobel began choosing winners in 1901, and for almost as long, some of its choices have been assailed as politicized, parochial or just misguided.” the New York Times wrote. (view source)

A communications scholar, Robert Terrill also wrote:

Throughout the campaign, Obama’s opponents had mocked him as an “international superstar with no accomplishments” and the awarding of the prize based on admittedly slim accomplishments seemed likely to invite similar assessments. As one former member of George W. Bush’s administration put it, the prize easily could become “a gift to the right.” (view source)

There ‘s also criticism about granting the Peace Prize to a president whose country was embroiled in war. Obama gave a speech at Oslo, Norway, for his winning of the Nobel Peace Prize.

“Still, we are at war, and I’m responsible for the deployment of thousands of young Americans to battle in a distant land. Some will kill, and some will be killed. And so I come here with an acute sense of the costs of armed conflict — filled with difficult questions about the relationship between war and peace, and our effort to replace one with the other.” (view source)

2012: The European Union

The European Union is a political and economic union of 27 member states that are located primarily in Europe. The purpose of the EU is to “aim to ensure the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital within the internal market; enact legislation in justice and home affairs; and maintain common policies on trade, agriculture, fisheries, and regional development.” (view source)

The EU received Nobel Peace Prize in 2012, “for over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe,” according to the award committee. (view source)

Although the EU won the prize, there’s a lot of controversies over whether they deserve the prize. “Alfred Nobel said that the prize should be given to those who worked for disarmament,” said Elsa-Britt Enger, a representative of Grandmothers for Peace, in a Reuters report at the time. “The EU doesn’t do that. It is one of the biggest weapons producers in the world.”

Also, the EU, as an economic union they also had done sales and promotion of that’s on the opposite side of defending human rights:

“The Nobel prize-givers obviously discounted the EU’s ceaseless promotion of counter-terrorism, surveillance policies and security technology too, and with it the wholesale targeting of Muslims and other minorities in Europe. ” wrote by Ben Hayes. (view source)